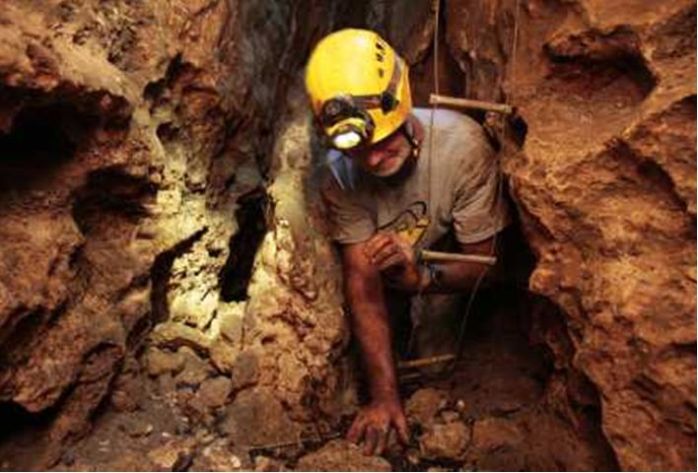

About 15 feet below ground, the writer makes his way through a tight spot in a cave during his trip to see evidence of falling groundwater levels in the region.

- Has the natural rainwater recharging system been diverted to Stormwater discharge?

RWH and gray water use will provide for a more natural recharge of our Ground Water and Aquifer resources.

- Has the use of underground water resources for irrigation and residential and Industrial development dried up our natural Aquifers?

Require agricultural users to create their own reservoirs and Industrial washing applications to also require private reservoirs and promote RWH and greywater use.

- Do these activities contribute to the increase of Sinkholes? Without a doubt!

See the following news article relating to the above photo.

Dry empty caves offer to grim proof of Tampa Bays groundwater decline

By Dan DeWitt, Times Columnist May 20, 2012

In Print: Sunday, May 20, 2012

In Thornton’s Cave, in southern Sumter County, you see beams of light streaming through holes in the ceiling, worn by thousands of years of steadily flowing water.

You see that the bottom half of the tunnel is almost as white as chalk, scoured by that same steady flow.

At the end of the one-third-mile-long cave, you see where the spring run once emerged. And you see that the run’s bed is not only dry, but covered by grass, weeds and opportunistic seedlings.

“I used to be afraid of this cave because you had to worry about cottonmouths and alligators,” Robert Brooks said with a shrug, meaning, obviously, that’s not a problem now.

Brooks, 38, has been wriggling into every crack in the earth he could find since he was a 10-year-old kid growing up in Brooksville.

We hear from the Southwest Florida Water Management District about the steadily declining groundwater levels, now nearly 2 feet below the bottom of the normal range for this time of year.

Brooks, one of the most experienced cavers in the state, recently led me and Times photographer Will Vragovic to see this decline.

Our view under the ground — at Thornton’s and at Crumbling Rock Cave in southern Citrus County — was as grim as the sight of the steadily shrinking rivers and lakes on the surface.

Or more so, because groundwater isn’t supposed to be as prone to fluctuation and is, of course, the source of almost all of the state’s drinking water.

One other thing, unsurprisingly, is the same above ground and below: the cause of the falling water levels, which is pumping and a long-term slump in rainfall.

Both caves are in Swiftmud’s Northern District, which includes Hernando and five other counties to the north and east. There, the amount of water pumped increased by 42 percent, to 163 million gallons a day, between 1990 to 2006, when demand started to decline slightly because of the flagging economy.

The historical average rainfall, compiled over the past three decades, is 53.5 inches per year. Since 1990, the annual total has been less than that 14 times, including each of the past six years.

Of course, back in the 1960s, that historical average was at least 2 inches higher, about 55 inches, a mark hit even less frequently in recent years.

So by visiting the cave in the middle of a severe drought, we weren’t seeing rare conditions, but ones that are recurring again and again.

“It’s like we’re in a drought, things briefly improve, and then we’re back in it again,” said Granville Kinsman, manager of the district’s hydrologic data section.

Kinsman also produced data showing that average rainfall was on an upward trend before 1960, suggesting the more recent downward one is part of a natural cycle.

Other theories are that the decreasing rainfall is tied to the loss of wetlands in Florida — “the rainmaking machine,” former Swiftmud executive director Sonny Vergara called it. Or that it’s related to global climate change.

But at this point, nobody really knows. And nobody I talked to at either Swiftmud or the much better-funded South Florida Water Management District has made a concerted effort to find out.

Which can’t go on.

Because whatever amount of pumping the district is allowing is too much.

It would probably be too much even if we were receiving steady doses of normal rain. It’s definitely too much if we’re dealing with a long-term decline.

Which is sure what it looks like underground.

The entrance to Crumbling Rock is a little like an old-fashioned well — a vertical shaft barely big enough to fit a bucket — and it used to lead directly to water.

Once Brooks had dropped a cable ladder down the shaft, and we had climbed down, he pointed to a coffee-colored water line that showed the usual level of the former underground stream.

“You would have been crawling with your chin just above water,” said Brooks, who has been exploring this cave for the past six years.

Every year, the water level has dropped, and on our visit we encountered only a few puddles and some ankle-deep mud.

“With the rain we’re getting, we’re ending every year in a deficit, and yet we’re taking the same amount out,” Brooks said.

“If you treated your bank account that way, you’d be broke. And our aquifer is broke.”

Maybe not yet. But it’s getting there.

Leave a comment